Adam Baruch | 99

Joshua Griffit: Behind All This, No Great Happiness Hides

By Adam Baruch

On Joshua Griffit’s attitude to “the surface”, on his fascination with the trivial, on his use of “ready-made painterly sentences” – and on his attitude to the misleading, the beautiful, the beautified, the artificial, stylization, mannerism, eclecticism, the model * On the unclosing distance between Griffit’s oeuvre and the central currents of contemporary Israeli art * Joshua Griffit: a majority of one in Israeli art.

The title, “Behind All This…”, is a paraphrase of a line by Yehuda Amichai. Even if Joshua Griffit’s painting has no real affinity to Amichai or to modern Hebrew Poetry in general – except for a certain affinity to Aharon Shabtai that finds expression in the painting Bed which is dedicated to him, “the bed” being a proclaimed physical-intellectual region in Shabtai’s verse – I have chosen a title that can misleadingly suggest that Joshua Griffit is as-it-were, and nonetheless, connected with Israeli poetry, etc., etc.

Misleading? Why mislead? Also because Griffit’s painting misleads, engages in misleading. The beautiful that misleads. The elegance that misleads. Griffit beautifies the beautiful. He both accentuates it and exaggerates it. Griffit also specializes in walking on the brink of exaggeration. In another second this is already not a remark on cloying sweetness, this is cloying sweetness. But it is a remark on. In another second Griffit is already immersed in exaggeration itself, but no he is not immersed, because he guards himself.

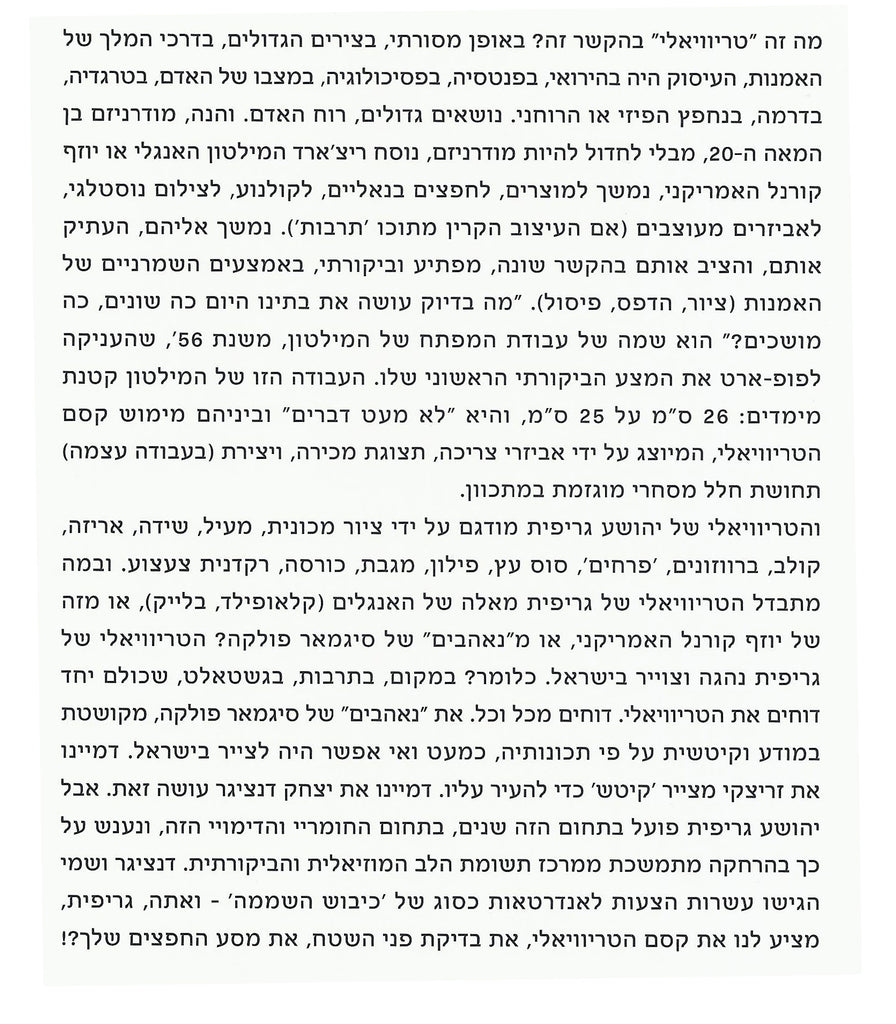

And behind all Joshua Griffit’s painted beauty and elegance. No great happiness hides. The painted objects, the painted figures, the composition, the “painted story” – all these, in Griffit’s work, are both “they”, and something which is not “they”. They are something that becomes transformed, As one views it, into an additional something: into an illumination of the brittleness and the fallaciousness of the beautiful, and into a refined ridiculing of representations of abundance, happiness, comfort, nostalgia, design, domestic order, “art”. Griffit both builds and undermines the beautified. What is “beautified”? What is made more beautiful that it really is. Artificially beautiful. Something that has been beautified so that it may represent the beautiful, for a brief moment.

For quite a number of years now I have been following Joshua Griffit's work from a semi-distance. I keep his catalogues, go and see his exhibitions, accumulate him in my private memory as an outsider in Israeli are and a fellow-traveler in international art. And for some time I have wanted to be involved in a real exhibition of his through a text that attempts to explicate him, to map him, and to produce a context for him, a context that in not strained.

Griffit touches quite a few visible contexts. Ornamental? Light-fantastic? Erotic-theatrical? Painting which simulated a voyage (all these ships, boats, cars)? Painting which is a “show of objects” (all these garments and accessories)? Painting in praise of eclecticism (the collection of objects and the collection of remarks and the collection of precedents)? Painting in praise of the manneristic gesture (opposite the gesture of the local Lyrical Abstract which for years was the obligatory canon)? Painting that is heaped, abundant in details, decorated like “a Nigger cemetery” (Wallace Stevens’ image), to cover the “nothingness” and the “void”? Modern Western fear in face of the “void”? Hyper-Realism, or rather a simulacrum of Hyper-Realism, which still stubbornly insists on persisting? Do the “geometrical” signs, which accompany a considerable portion of the works, potentially indicate to us that the painting is a “model”? Nostalgia for its own sake (all these ornate stickers, souvenirs of fashion and symbols of sweetness)? A slow and meticulous dismantling of the components of kitsch?

* * *

The sum total of Griffit's painting is a prolonged remark on the term “surface”. From this stems Griffit’s coloring. From this stems the quasi-extroverted and quasi-immediate lexicon of images. From this stems the sense of “design”.

From this, too, stem the remarks on the history of are as a reservoir of “ready-made sentences” (an ethics which has become an aesthetics that is always available and exempt). The history of art as formulated by Francis Bacon, Allen Jones, Picasso, Robert Motherwell, Morley, Matisse, De Chirico, Cornell, or a portion of the American Hyper-Realism, and I have not listed all the genealogy.

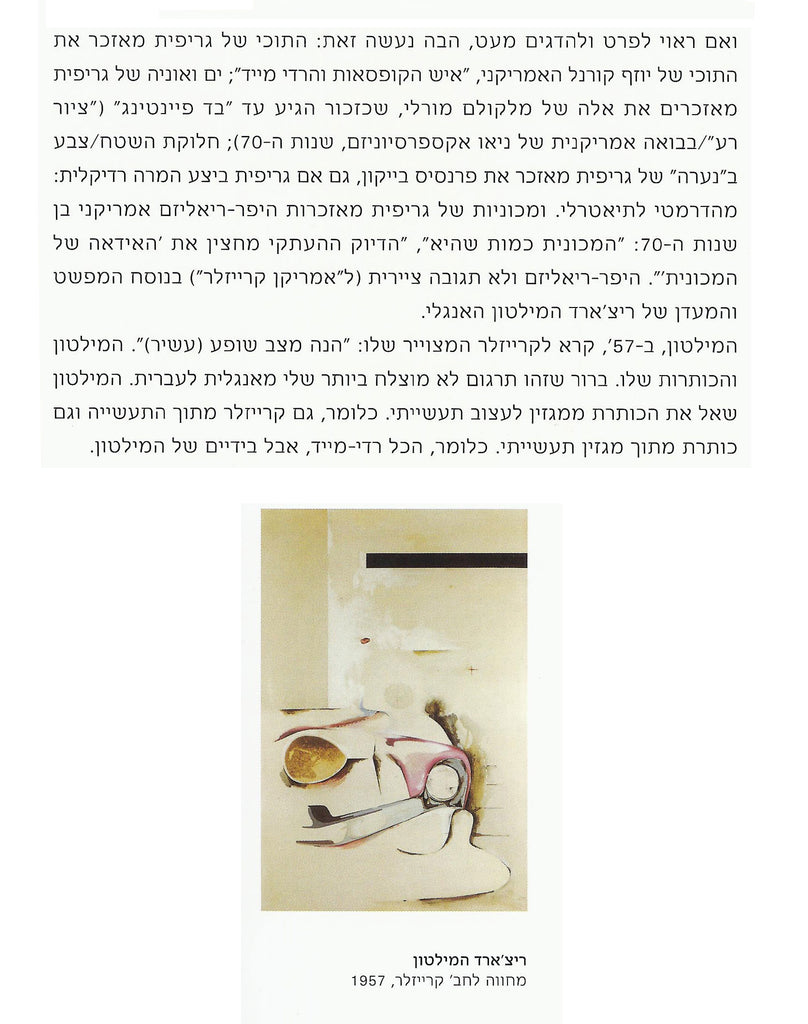

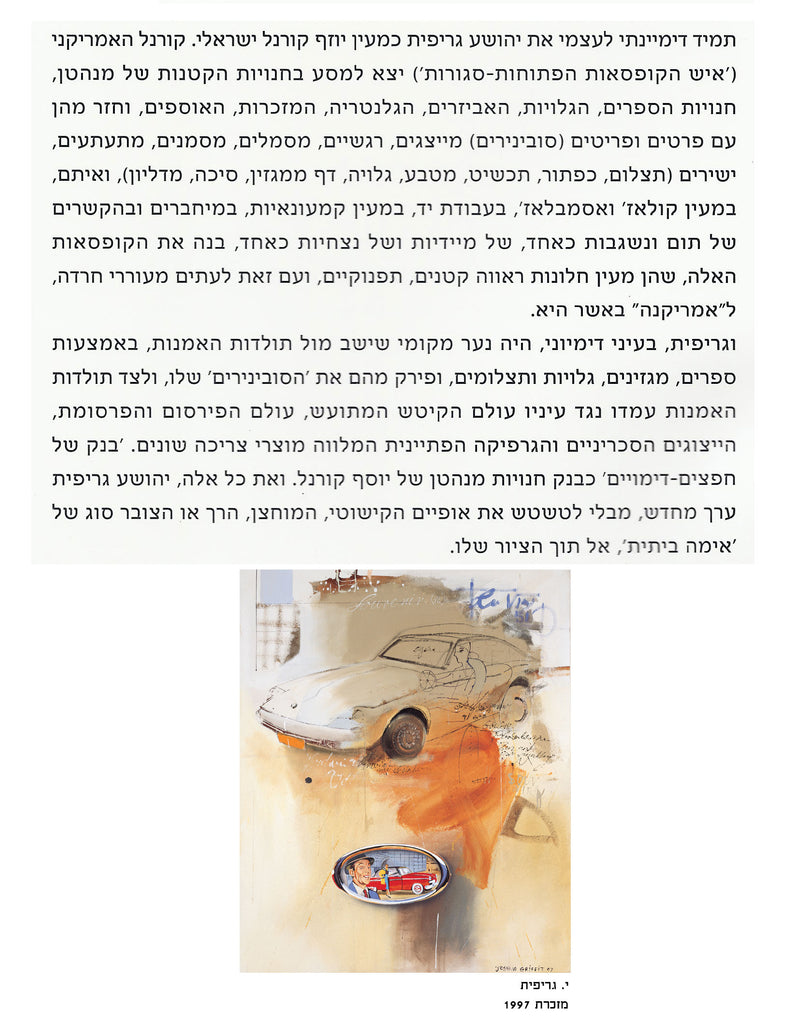

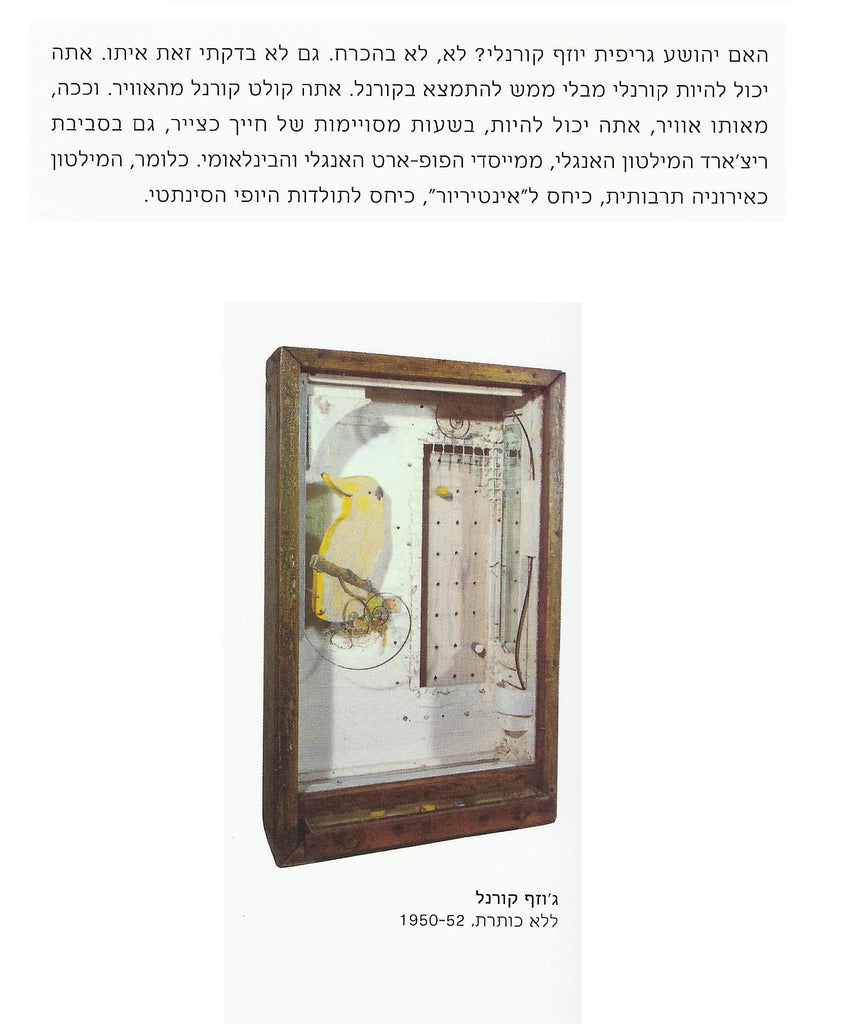

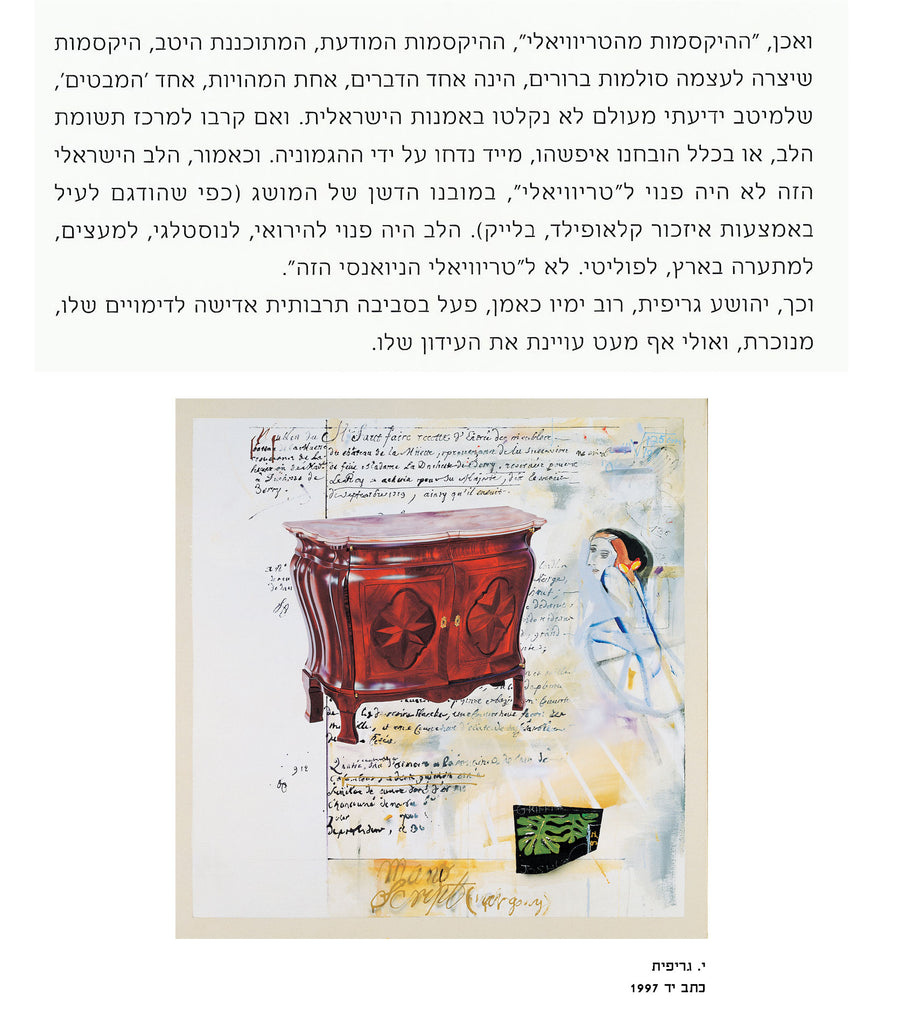

And if it is fitting to detail and demonstrate this a little, let’s do it: Griffit's parakeet echoes the parakeet of the American Joseph Cornell, “the man of the boxes and the ready-mades”; Griffit's sea and ship echo those of Malcolm Morley who, we will recall, arrived at “bad painting” (an American simulacrum of Neo-Expressionism, the ‘70s); the color/area division in Griffit's Girl echoes Francis Bacon, even if Griffit has made a radical transformation: from the dramatic to the theatrical. And Griffit's cars echo the American Hyper-Realism of the ‘70s: “the car as it is”, the accuracy of the copying expresses ‘the idea of the car’”. Hyper-Realism, not a painterly response (to American Chrysler) along the abstracting and refining lines of the Englishman Richard Hamilton. Hamilton, in ‘57, called his painted Chrysler here is a Lush Situation. Hamilton’s titles. He borrowed this title from an industrial design magazine. I.e., a Chrysler from industry, and a title from an industrial magazine. I.e., everything is ready-made, but handled by Hamilton.

* * *

I have always thought of Griffit in some connection with an English group (Jones, Blake, Caulfield, Hamilton) that I like a lot, to the point that I have accumulated literature about it, have tried to see group and solo exhibitions by its members, and have even collected a few works by members of this group (prints, small collages), which is not formally a group, but rather a group which I created for myself as a somewhat loose act of cataloguing. And I’ve always thought of Griffit in connection with the American Joseph Cornell, who squeezed the “mythological” character out of “trivia” and imprisoned the trivial and the mythical in small display boxes. And in the ‘80s and the ‘90s, while cruising through are books, catalogues and exhibitions, I marked affinities of style and material between certain non-Israeli artists (Sigmar Polke, David Salle, and here and there Audrey Flack) and certain works by Joshua Griffit. And I will not be wrong if I say that I have never found such affinities between Griffit and any Israeli artist. Thus, and for this reason, Polke, Salle, the English group, and of course Joseph Cornell, are very much presenced in this essay. There is a goof Hamiltonianity present in the background of Joshua Griffit, even though Griffit himself is not “Hamiltonian”. A good hamiltonianity? In what sense precisely? In the sense of the very act of contemplating the “surface” that is represented by functional objects (a car), by the painterly-graphic propaganda (a magazine cover) which assists in their distribution and sale, by the injection of eroticism, by means of stylization (the commercialized representation), after the functionality and the efficiency of the object have already been achieved. Griffit’s painting, in its essence, is also a constant remark on “stylization”, while making use of it and while presenting it as the “surface”. By the way, this is also the same “stylization” which is absent from Israeli life, or at least was absent until a decade and a half ago. It was absent also because there was no room for it in this Israeli life, since the early ‘50s, until a decade and a half ago. I.e., Griffit's painting, Which also deals with “stylization”, attests to the prolonged local lack of it, And slightly ridicules its “wild” emergence here in the past decade and a half. What is not “stylized” today? You suddenly can’t find even a spoon that isn’t “designed”.

* * *

I’ve always imagined Joshua Griffit as a kind of Israeli Joseph Cornell. The American Cornell (“the man of the open/closed boxes”), set out on a journey in the little shops of Manhattan – shops that stock books, postcards, haberdashery, souvenirs, collections, and returned with items (souvenirs) and details that were representative, emotional, symbolizing, signifying, delusive, direct (a photograph, a button, a trinket, a coin, a postcard, a page from a magazine, a pin, a medallion), and with them, in a kind of collage and assemblage, manually, in a kind of retailing approach, using connections and contexts of both sublimity and innocence, of both immediacy and eternality, he built those boxes, which are a kind of small, indulgent, but at the same time horrifying showcases for “America”, wherever it be. And Griffit, in my imagination’s eyes, was a local boy who sat opposite the history of art, by means of books, magazines, postcards and photographs, and picked out his own “souvenirs”, And beside the history of art was faced with the world of industrialized kitsch, the world of publishing and of advertising, of the saccharine representations and the seductive graphics that accompany various consumer products. A “bank of objects-images” like Joseph Cornell’s bank of Manhattan shops. And all these – Joshua Griffit re-edited them, without obscuring their character as decorative, extroverted, soft or accumulating a kind of sort of “domestic horror”, into his own painting.

* * *

Is Joshua Griffit Joseph-Cornellian? No, not necessarily. Not have I checked this with him. You can be Cornellian without being really versed in Cornell. You absorb Cornell from the air. And so, from the same air, you can, in certain hours of your life as a painter, be in the vicinity of the Englishman Richard Hamilton, one of the founders of English and international Pop-Art. I.e., Hamilton as a cultural irony, as a relation to an “interior”, as a relation to the history of synthetic beauty.

* * *

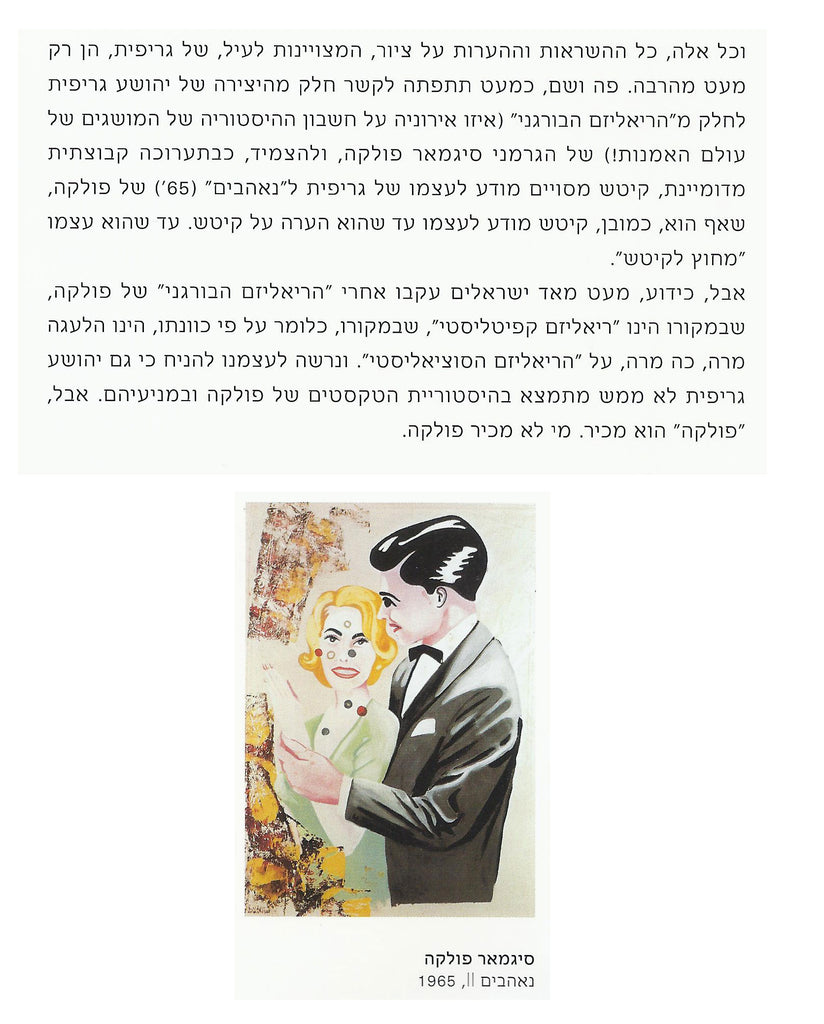

And all these, all Griffit's inspirations and remarks on painting noted above, are only a few out of many. Here and there, you will almost be tempted to connect part of Joshua Griffit's oeuvre with part of the “Bourgeois Realism” (what an irony at the expense of the history of the art world’s concepts) of the German Sigmar Polke, and, as in an imagined group exhibition, to hang a particular self-conscious kitsch of Griffit's beside Polke's Lovers II ('65), which too, of course, is self-conscious kitsch to the point of being a remark on kitsch. To the point of being “outside kitsch”.

But, as we know, very few Israelis followed Polke’s “Bourgeois Realism”, which in its original form was “Capitalist Realism”, which in its original form, i,e., in its intention, was a bitter, so bitter ridiculing of “Socialist Realism”. And we may allow ourselves to assume that Joshua Griffit, too, is not well versed in the history and motives of Polke’s texts. But – he knows Polke. Who doesn’t know Polke?

* * *

Writing about Joshua Griffit, too, is a kind of cruising. So far, only a few extensive articles have been written about Griffit's art. Dr. Gideon Ofrat have written fine and deep-delving articles about him, and now, with the exhibition at the Museum of Israeli Art, Ramat-Gan, curated by the Museum’s director, Meir Ahronson, when you examine the Griffit file in the archives of Israeli art writing, the findings are meager: very little interest in Griffit, in Griffit's kind. And let the truth be said: Griffit's kind is outside the agenda of the “directed” (i.e., the displayed, the accumulated, the distributed) Israeli art. The museums, the leading galleries, the critics and the media, let’s say of the past 20 years, do not deal with “this kind”. Why?

* * *

And thus, in the absence of an Israeli context for Griffit, writing about him sends you cruising outside. A little in the direction of Sigmar Polke. A lot in the direction of Joseph Cornell. Very much in the direction of “the magic of the trivial”. When this magic is interpreted by a real artist (such as Joshua Griffit or the Englishman Blake) entire worlds unfold and spread out from it: art, social criticism, compassion. We will return further on to “the magic of the trivial”. In this cruising you will meet “models” of a kind as well: David Salle’s Pink Tea-Cup, ’95: industrial objects, kitsch, advertising, a kind of collage, a nuance of commercialized eroticism. Salle, we will recall, has been exhibited at the Tel-Aviv Museum. But – Griffit is far from Salle, in most of the formal and emotional senses.

And, all in all, this cruising in Griffit’s tracks, which is my own, private thing, brings you back to Joshua Griffit as a “source”, with and in spite of all the affinities and echoes, Griffit, who has processed data from the history of art, is a sovereign artistic personality. And Griffit's “fascination with the trivial” (Cornell, Polke, Hamilton, Caulfield, Blake) is Griffit's own.

The “fascination with the trivial” is, in my opinion, a most real characteristic of Griffit's oeuvre. There Griffit's gaze and his hand balance themselves into a single action, make themselves precise.

* * *

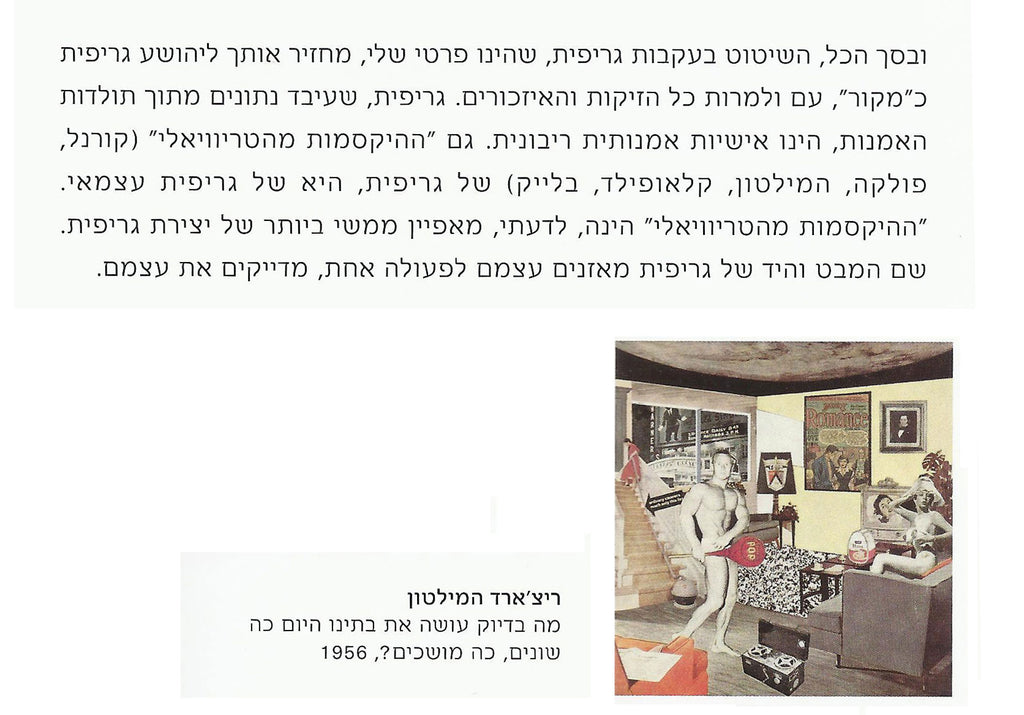

What is “trivial”, in this context? Traditionally, on the major routes, on the main highways of art, artists have engaged in the heroic, in fantasy, in psychology, in the human condition, in tragedy, in drama, in the desired, be it physical or spiritual. Great subjects, the human spirit. And then, 20th-century Modernism, without ceasing to be Modernism, became attracted – a’ la the Englishman Richard Hamilton or the American Joseph Cornell – to products, to banal objects, to movies, to nostalgic photography, to designed accessories (if the design somehow projected “culture”). Became attracted to them, copied them, and placed them in a different, surprising and critical context, in the conservative means of art (painting, printmaking, sculpture). “Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing?” is the name of Hamilton’s key work, from ’56, which gave Pop-Art its first critical program. This work by Hamilton is small in dimensions: 26 cm. By 25 cm., and it is “quite a few things”, among them actualization of the magic of the trivial, which is represented by consumption articles, display for sale, and the creation (within the work itself) of a sense of a deliberately exaggerated commercial space. And Joshua Griffit's trivial is demonstrated by his painting a car, a coat, a cabinet, a package, a coat hanger, ducklings, “flowers”, a rocking-horse, a little elephant, a towel, an armchair, a toy ballerina. And in what does Griffit's trivial differ from those of the Englishmen (Caulfield, Blake), or that of the American Joseph Cornell, or from Sigmar Polke’s Lovers? Griffit's trivial was conceived and painted in Israel. I.e.,? In a place, in a culture, in a Gestalt, all of which reject the trivial. Reject it completely. Sigmar Polke’s Lovers, consciously ornamented and kitschy in its qualities, would have been almost impossible to paint in Israel. Imagine Zaritsky painting “kitsch” in order to make a remark about it. Imagine Danziger doing it. But Joshua Griffit has been working in this domain for years, in this domain of materials and imagery, and has been punished for it by a prolonged ostracism from the center of museum and critical attention. Danziger and Shemi submitted tens of proposals for more monuments as a kind of “Conquest of the Wilderness” – and you, Griffit, offer us the magic of the trivial, the examination of the surface, your journey of objects?!

* * *

And indeed, “the fascination with the trivial”, the conscious, well planned fascination, the fascination which has created clear scales for itself, is one of the things, one of the essences, one of the “gazes”, which in my opinion has never been absorbed into Israeli art. And if they ever did get close to the center of attention, or were even noticed somewhere, they were immediately rejected by the hegemony. And, as already stated, this Israeli heart did not have room for the “trivial”, in the rich sense of the term (as demonstrated above by means of the reference to Caulfield, Blake). This heart had room for the heroic, the nostalgic, the empowering, the involved in the country’s life, the political. Not for “this nuanced trivial”. And thus, Joshua Griffit, most of his days as an artist, has worked in a cultural environment that is indifferent to his images, that is alienated, and perhaps even a little hostile to his refinement.

* * *

Inspiration, precedents, processing, independence. Joshua Griffit incessantly salutes the history of art. He does not quote, he salutes. I.e., this is not the kind of quotation that is saturated, that takes upon itself all the ethics and the aesthetics of the precedent, or confronts it forcefully, but rather a light salute, evoking associations, ironic, and often even ingenious. For example, Hamilton, in his “Chrysler”, both quoted and saluted Marcel Duchamp (and the mechanical-sexual complex), while Griffit already chooses the “Chrysler” of American Hyper-Realism, which isolates the car, cleans it of low appendages, and empowers it.

* * *

From all this it is evident that Joshua Griffit very rarely “salutes” Israeli art. He does not “salute” Zaritsky, Stematsky, Danziger, Shemi, Rubin or Gutman, the history of local nostalgia, or local “design”. An outsider boy looking outside. This very non-saluting to the local forms and the local canons and the abovenamed personages is Joshua Griffit's longstanding and reasoned position towards the culture and the art of this Israeli place, towards the hierarchical ranking that has become established here, towards the painterly essence that has taken shape here and become dominant here. Griffit does not respond to Zaritsky, for Griffit has non-Zaritskyan sources of inspiration. And, as already stated (and it’s right to repeat and stress this), Joshua Griffit is thus quite lonely in the Israeli art community. He has no local predecessor. He has no local painterly inspiration. And he has no partners here. An Israeli without fellows. Not Tzuba (Zaritsky/Abramson), not The Binding of Isaac (Bezem/Kadishman), not coded ideology (Cohen Gan/Zvi Goldstein), not political (Ruth Schloss/David Reeb), not involved (Avraham Ofek/Jan Rauchwerger). What does he have? Himself.

By the way, in recent years, here and there, you see in Griffit's painting a kind of (expressive or lyrical) abstract “swish”. What is this? It is not the beginnings of a migration from the precise to the abstract. It is a “souvenir” which Griffit has borrowed in order to implant it in his painting, to amuse himself. The abstract itself, after its peak, has, in certain senses, been stored in the drawer of trivia, and Griffit, as we’ve said, is fascinated with trivia.

Adam Baruch 1999