Gideon Ofrat | 95

Acrobatics Above the Chaos

Gideon Ofrat

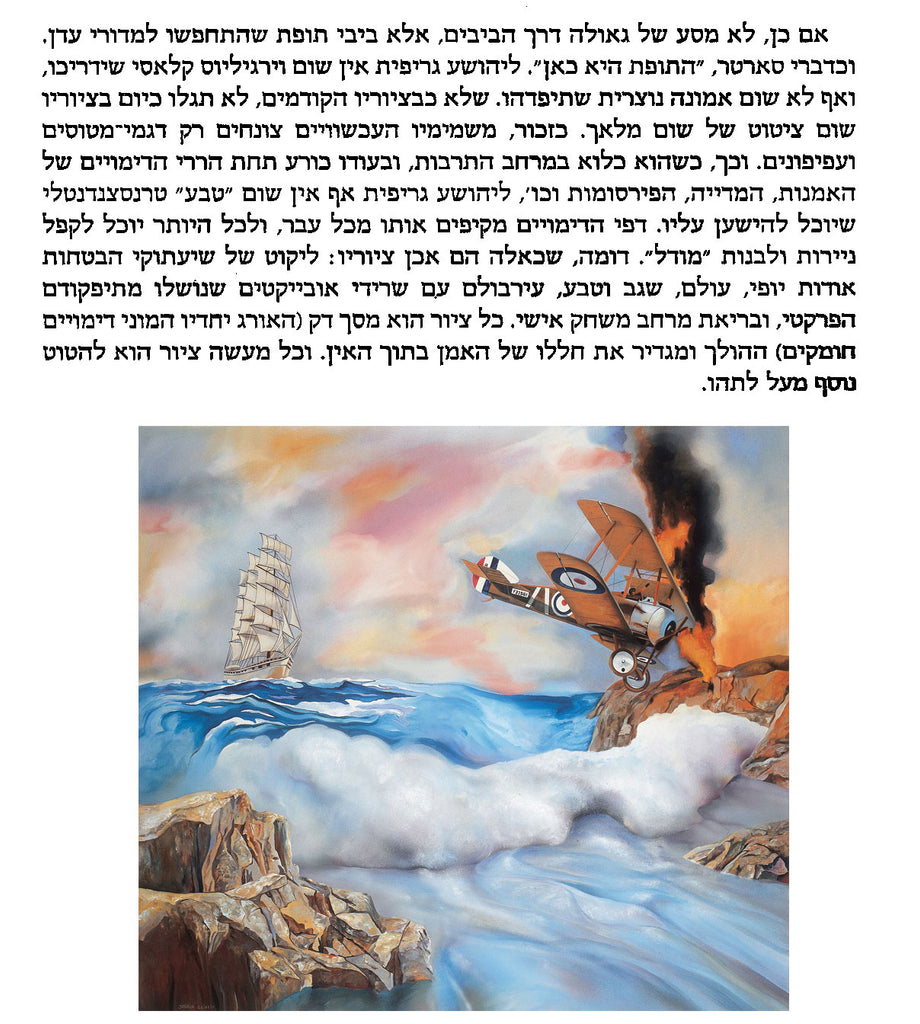

The bow that Joshua Griffit paints no longer shoots any arrow at any target. Actually, from the outset it was only a children's toy. Now, the bow-branch is displayed in its humiliation, stringless, broken, and stained. It carries with it only longings for a distant horizon of an arrow that is no more, and memories of the arched "heroic" stretching. What remains for the bow to represent now if not one more line in a formal composition? Here it is then, in the role of the diagonal, and as a substitute for the airplane-wing that has dropped off. The airplane, or the model airplane, is in a diving posture, and Griffit attaches the bow-branch to it as a crutch. Within himself he knows: the plane is falling, the flight to ... has failed.

An increasing degree of existential weariness and of loss of hope is depicted in Joshua Griffit's paintings of the past two years. In 1990, in the introduction to his catalogue, we expatiated on his "journeys" to distances of the imagination, after discovering in almost every one of his paintings vehicles which take him/ us from "here" to "there".

Joshua Griffit travels. For ten years now he has been traveling in his paintings: by cars, by tram, by ship, by coach, by motorcycle, by planes, by horse, by sailboat or motorboat, even by gondola. To travel, far, and at any price. And always - by models of these vehicles - by their plastic toys, their advertisement photographs, even by famous paintings of boats [...]. Joshua Griffit travels with the aid of models, for his journey is a journey of simulation, a journey of art and about art.

Five years later, we find that the journeys are over, and that Griffit's space of simulation has become limited mostly to the home, to the implements and everything that is stored at home. For now we stand facing a shattered boat, or a sinking boat, or a falling plane, and, as a rule, we almost do not meet vehicles. A handful of models of kites and airplanes have taken the place of the grand theater of voyaging. On the other hand, we meet lots of shirts, clothes-hangers, "Burda" patterns, protective clothing, a masked ball, red shoes, a fan, wallpaper and lace, and even a parakeet (probably a stuffed one or a cast toy) – which still leave us in the sphere of the ornamentation of the "domestic" show, spectacle (imposture) and simulation, and does this domestic parakeet hint at the caging/ domestication ofthe artist who has ceased from his travelings?

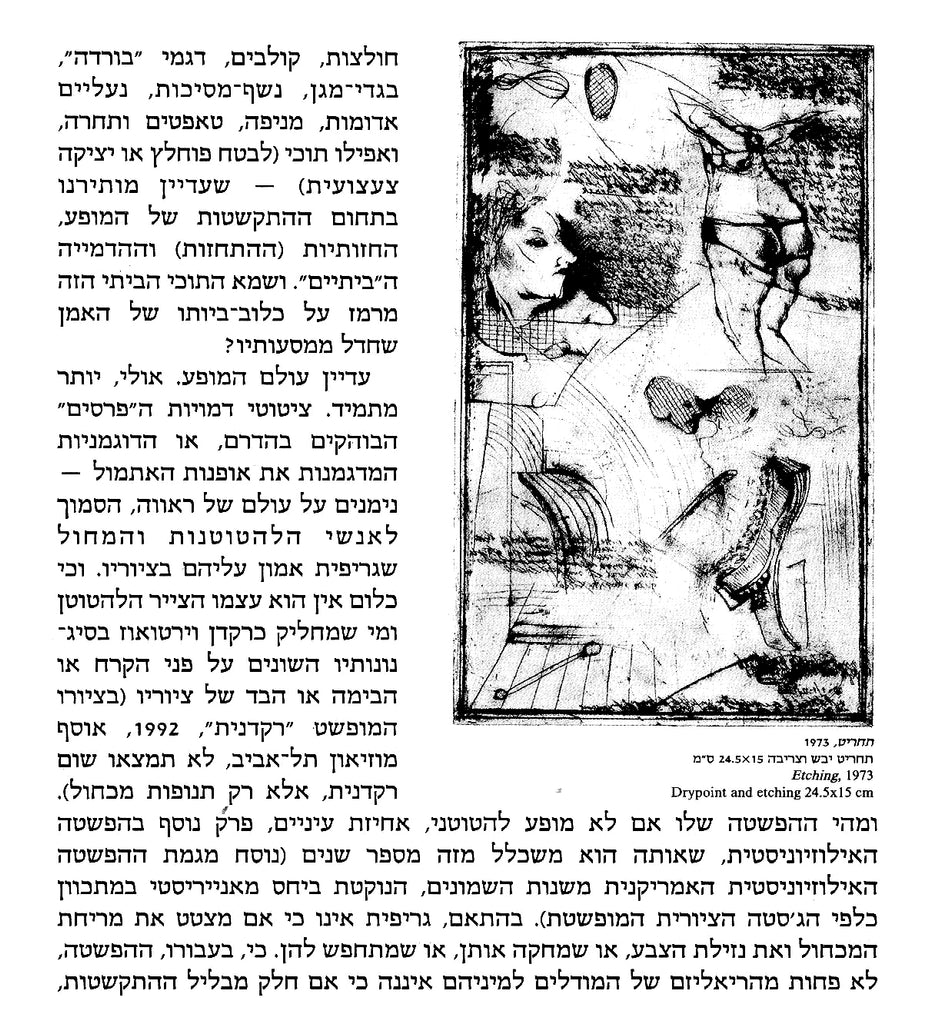

Still the world of the show. Perhaps more than ever before. The quotations of the glossy embossed "scraps", or the fashion models modeling yesterday's fashions, all belong to the world of spectacle, which is close to the acrobats and dancers whom Griffit so skilfully portrays in his paintings. And is he not himself the acrobat painter, who skates like a virtuoso dancer with his various styles over the ice or the stage or the canvas of his paintings (in his painting "Danseuse", 1992, Collection Tel Aviv Museum, you will not find any danseuse, only movements of the paintbrush).

And what is his abstraction if not an acrobatic show, an illusion, another phase of the illusionistic abstraction that he has been developing and improving for a number of years now (along the lines of the American illusionistic abstract trend of the eighties, which takes a deliberately manneristic approach towards the abstract painterly gesture)? Accordingly, Griffit is essentially quoting the brush-smear and the dripping of the paint, or is imitating them, or he is disguising himself as them. Because, for him, the abstraction, no less than the realism of the variety of models, is only part of the medley of ornamentation, the medley of imposture, which seeks to use the vain charms of the beautiful forms (whether realistic or abstract) to cover up the great emptiness behind him. Putting make-up on a corpse.

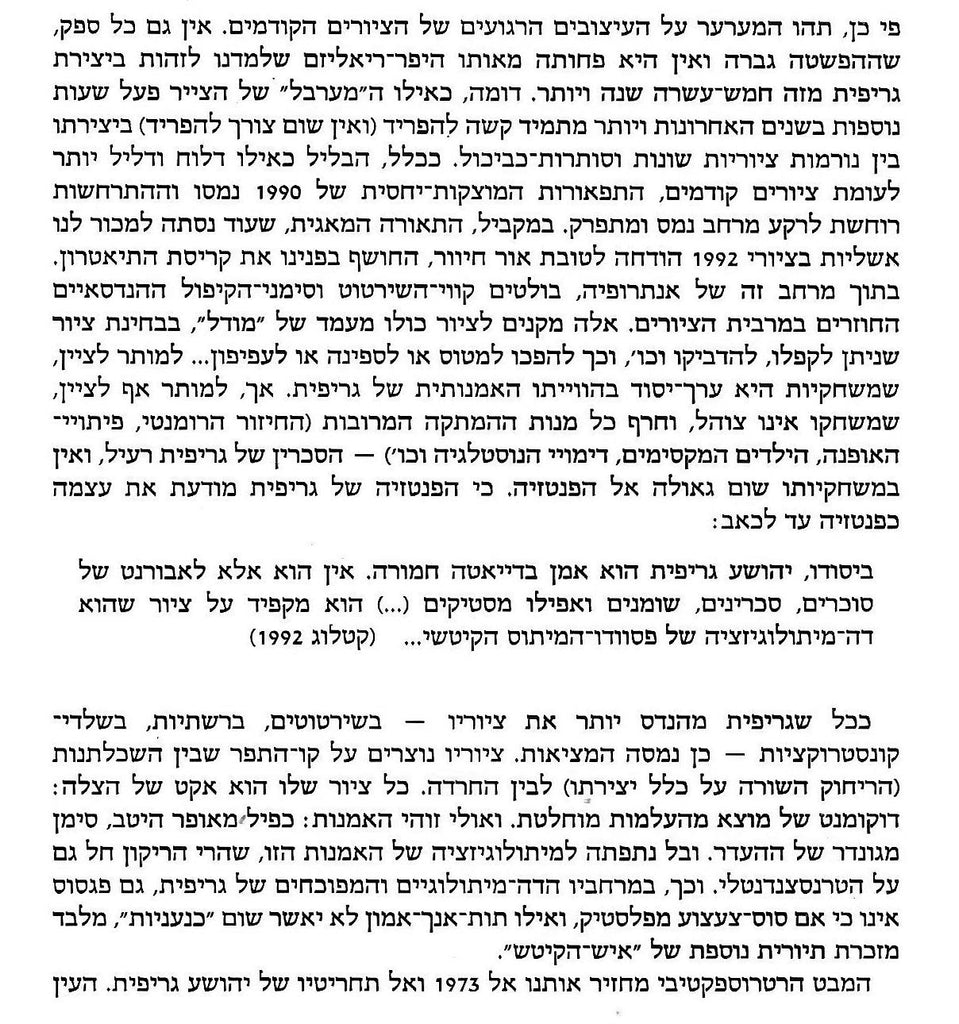

For, paradoxically, Joshua Griffit's ontology (theory of what is) confirms what is not. As great as is the quantity and profusion of the painted images, such is the quantity of the non-being. And when some functional object (such as a close thing, or a plank) slips into this nothingness, it is condemned to the mixing that dismantles, dissolves, and strips. For Griffit's one and only solid "is" is the pictorial "is" (from the history of which he also gleans pseudo-concrete images onto his canvasses - a still life, a sculpture, and the like). Meaningful, therefore, is the thickness of the paint in these "material" paintings, which are rich in lumps of paint, in mixtures with sand, etc., all of which confirm the ostensible isness. Except that this is a fictitious isness, of an autonomous formal space, which devours the objects of the world in the bowels of the artistic "as it were". In other words: Griffit's paintings affirm modernism (the expropriation of art from life) and postmodernism (the swallowing up of the materials of life in the artistic simulation) at one and the same time. As befits an artist whose artistic growth began in the late sixties, at the height of the modernist impaction on the local scene, and found himself flung into the postmodern spoof ery of the eighties.

A retrospective viewing of Joshua Griffit's paintings of the last decade will prove that the compositions of today are freer than ever, if not to say that they cast off discipline and reject order. A cold, restrained and sober chaos, we must hasten to emphasize; yet a chaos that undermines the serene designs of the earlier paintings. There is also no doubt that the abstraction has increased and is now no less present than the hyper-realism which we have learned to identify in Griffit's art for the past fifteen years or more. It seems as if the artist's "mixer" has been working overtime in recent years, and that it is harder than ever to separate (and there is no need to separate) between the various and ostensibly contradictory painterly norms in his work. As a rule, the amalgam appears thinner and murkier than in earlier paintings, the relatively solid decors of 1990 have dissolved and the action takes place on the background of a dissolving and decomposing space. Concurrently, the magical lighting, which in the 1992 paintings still tried to sell us illusions, has been rejected in favor of a pale light, which exposes before us the collapse of the theater. Prominent within this space of entropy are the geometrical drawing-lines and signs of folding which recur in most of the paintings. These accord the entire painting the status of a "model", in the sense of a painting that can be folded, pasted, etc., and thus to turn it into an airplane or a boat or a kite...

It is superfluous to note that play is a basic value in Griffit's artistic being. But it is also superfluous to note that his play is not gleeful, and despite all the numerous portions of sweetening (the romantic courting, the seductions of fashion, the enchanting children, the images of nostalgia, etc.). Griffit's saccharin is poisonous, and there is no redemption towards fantasy in his play. Because Griffit's fantasy is painfully conscious of itself as fantasy: “Fundamentally, Joshua Griffit is an artist on a strict diet. He is essentially a laboratory-worker of sugars, saccharins, fats and even chewing-gum [...] He insists on a painting that is a demy tho log i zing of the pseudo-mythos of Kitsch ...” (Catalogue 1992)

The more Griffit engineers his paintings - with geometrical drawings, with grids, with skeletons of constructions – the more the reality dissolves. His paintings are created upon the interface between intellectualism (the distantiation that suffuses the entire work) and anxiety. Each painting of his is an act of rescue: a document of emergence from absolute disappearance. And perhaps this is the art: a well made-up double, a dandified sign of absence. And let us not be tempted to mythologize this art, because the voiding also applies to the transcendental. And thus, in Griffit's sober and de-mythologized spaces, even Pegasus is only a toy horse made of lastic, while Tutankhamen will not approve any "Canaanism", apart from a tourist souvenir of "the Kitsch-man".

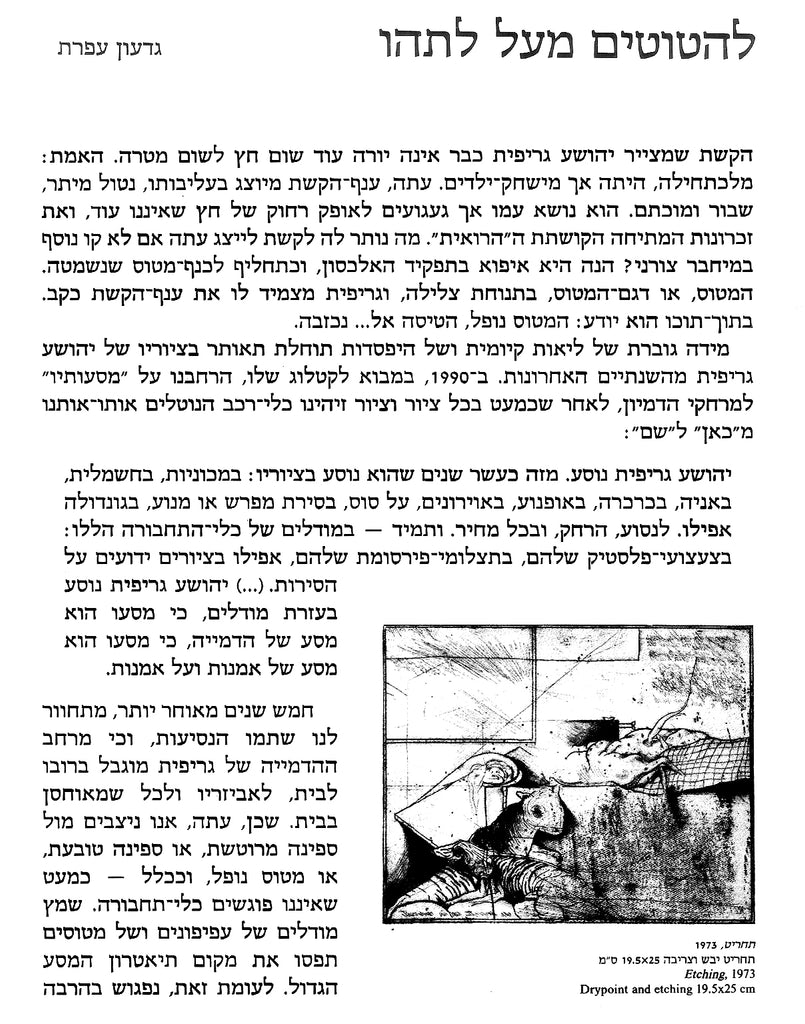

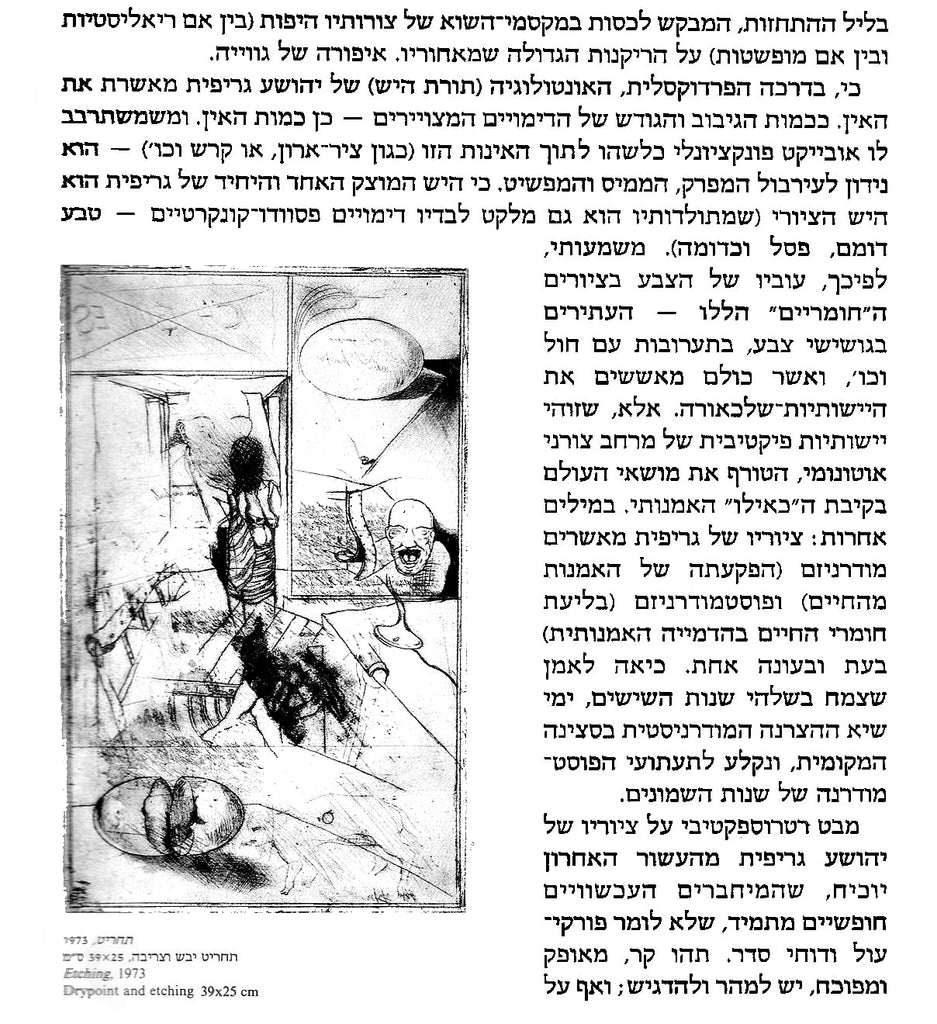

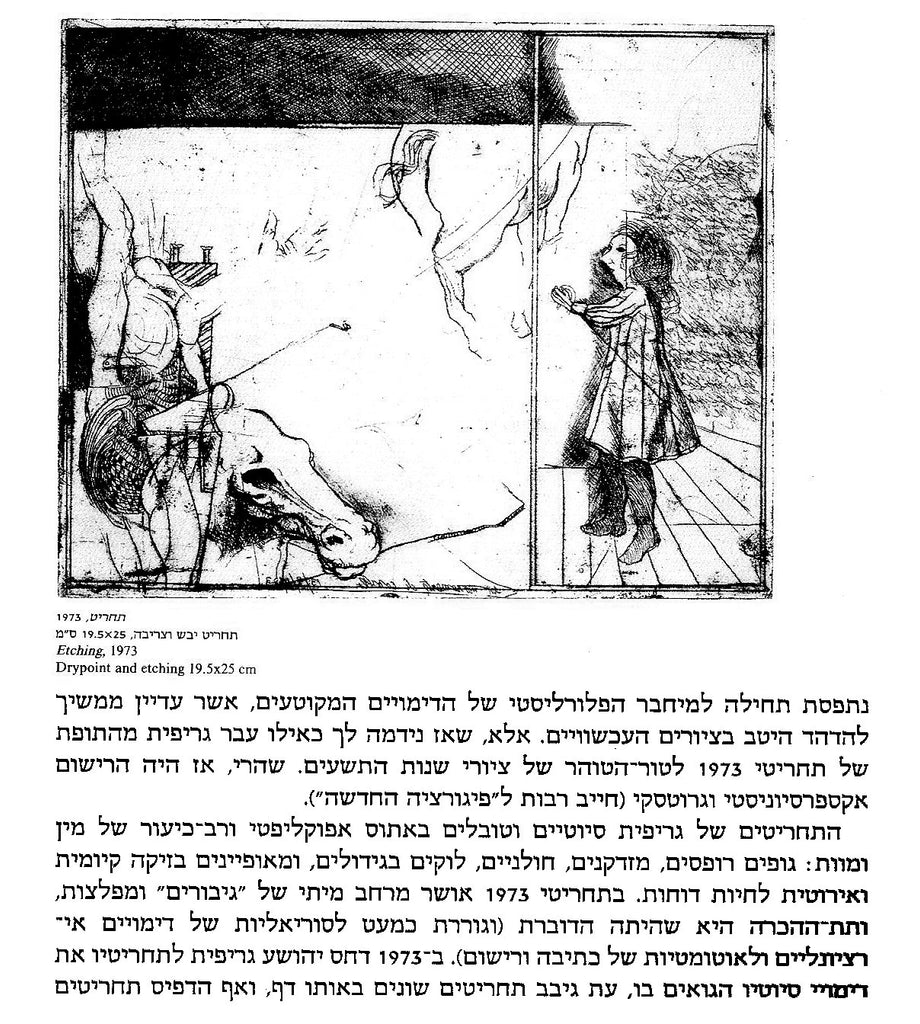

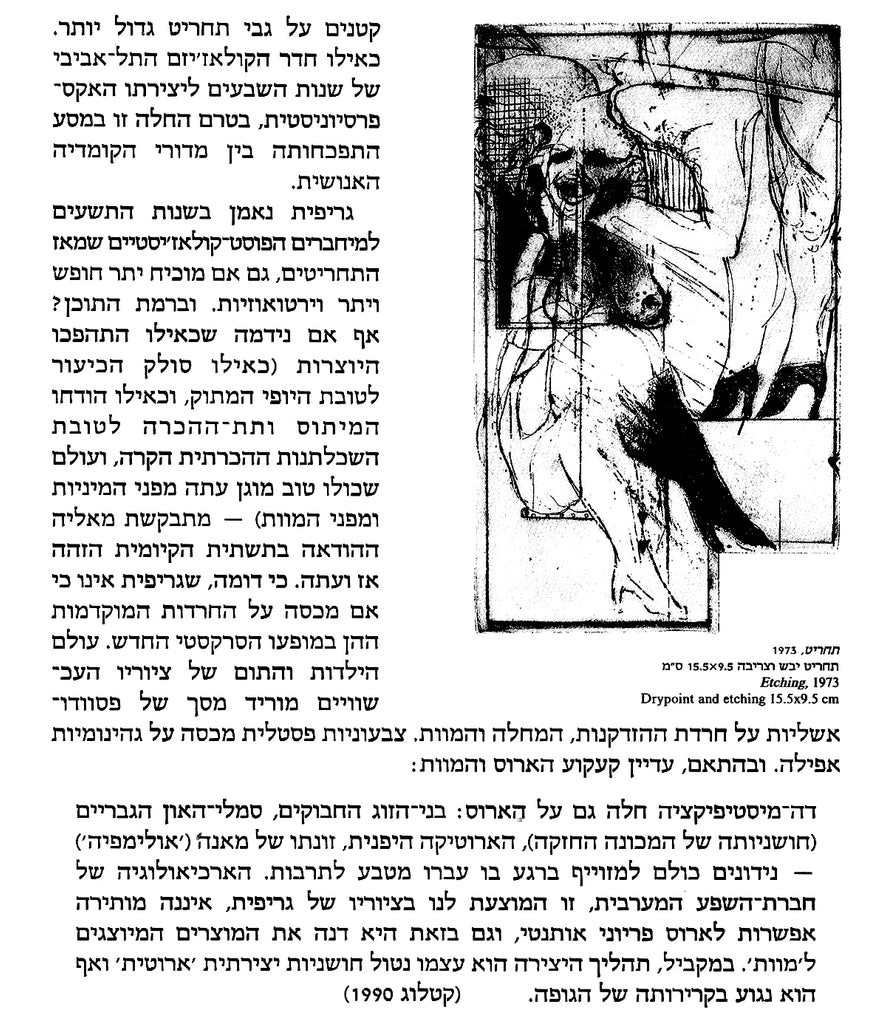

The retrospective view brings us back to 1973 and to Joshua Griffit's etchings. The eye is caught first of all by the pluralistic composition of the fragmented images, which still continues to resonate well in the recent paintings. Except that then it seems to you as if Griffit has passed from the inferno of the 1973 etchings to the age of purity of the paintings of the nineties. Because then the drawing was expressionistic and grotesque (owing much to "The New Figuration"). Griffit's etchings are nightmarish and are plunged in an apocalyptic and super-ugly ethos of sex and death: flabby, ageing, diseased bodies, suffering from tumors, and characterized by an existential and erotic affinity to repulsive animals. In the 1973 etchings, a mythical space of "heroes" and monsters was affirmed, and the subconscious was the speaker (which pulled to what was almost a surrealism of irrational images and an automatism of writing and drawing). In 1973 Joshua Griffit compressed the images of his burgeoning nightmares into his etchings, when he piled various etchings onto the same page, and also printed small etchings on top of a larger etching. It is as though the Tel-Aviv collagism of the seventies had penetrated into his expressionistic art even before the latter had begun its sobering journey among the spheres of the human comedy. In the nineties Griffit is faithful to the post-collagistic compositions that began with the etchings, even if he does evince more freedom and more virtuosity. And on the level of the content? Even if it seems as if the tables have been turned ( as if the ugliness has been banished in favor of the sweet beauty, and as if the myth and the sub-conscious have been deposed in fay or of the intellectualism and the death), there is no avoiding the admission of an identical infrastructure both then and now. For it seems that Griffit is only covering up those early anxieties with his new sarcastic show. The world of childhood and innocence in his present paintings brings down a screen of pseudo-illusions over the anxiety of ageing, disease and death.

A pastel coloring covers over the dark hellishness. And, accordingly, there is still the tattoo of eros and death: There is also a demystification of Eros: the embraced couple, the male signs of potency (the sensuality of the powerful car), the Japanese erotica, Manet's whore ('Olympia') - all are condemned to fraudulence from the moment they pass from nature to culture. The archaeology of the affluent society of the West, the society offered to us in Griffit's paintings, leaves no possibility for an authentic, fertile Eros, and in this too it condemns the products represented to 'death'. Concurrently, the creative process itself is without any 'erotic' creative sensuality, and it too is touched with the coldness of the corpse. (Catalogue 1990)

If so, this is not a voyage of redemption through the sewers, but the sewers of hell that have disguised themselves as the spheres of paradise. And, as Sartre says, "Hell is here". Joshua Griffit has no classical Virgil to guide him, nor any Christian faith to redeem him. In contrast to what appeared in his early paintings, you will not find a single quotation of even a single angel in his paintings today. As already mentioned, from his skies of today there fall only model planes and kites. And thus, caged in the space of culture, and still bowed under the mountains of images of art, the media, advertising, etc., Joshua Griffit also has no transcendental "nature" to lean on. The pages of images encompass him on all sides, and at the most he can fold papers and build a "model". It seems that his paintings are indeed like this: a gleaning of reproductions of promises about beauty, world, sublimity and nature, a mixing of remnants of objects that have been deprived of their practical function, and a creating of a personal play space. Each painting is a thin screen (which weaves together multitudes of elusive images) that increasingly defines the space of the artist within the nothingness. And each act of painting is one more act of acrobatics above the chaos.