Yivsam Azgad | 2018-2021

Joshua Griffit / Real time

Yivsam Azgad

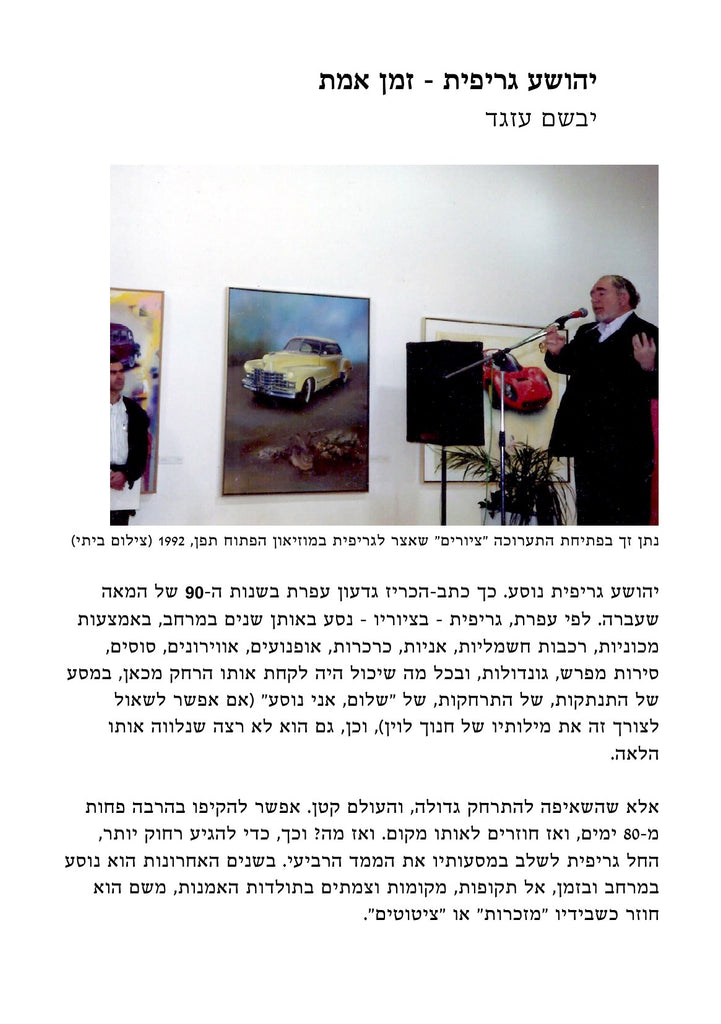

Joshua Griffit is a traveler. So wrote/declared Gideon Ofrat in the early 1990s. According to Ofrat, Griffit – in his paintings – traversed space during those years, using automobiles, electric trains, ships, carriages, motorcycles, airplanes, horses, sailboats, gondolas – everything that could take him far away from here, on a journey of disengagement, separation, moving away, of “Goodbye, I’m going” (if one can borrow for this purpose the words of playwright Hanoch Levin), and yes, he too didn’t want us to see him off.

But the desire to get away is great, and the world is a small place. It can be circumnavigated in much less than 80 days, after which the traveler returns to the exact same spot. Then what? So, to go farther, Griffit started to include in his travels the fourth dimension. In recent years, he has traveled across space and time, to periods, places and junctions in the history of art, bringing back with "souvenirs" or "quotes."

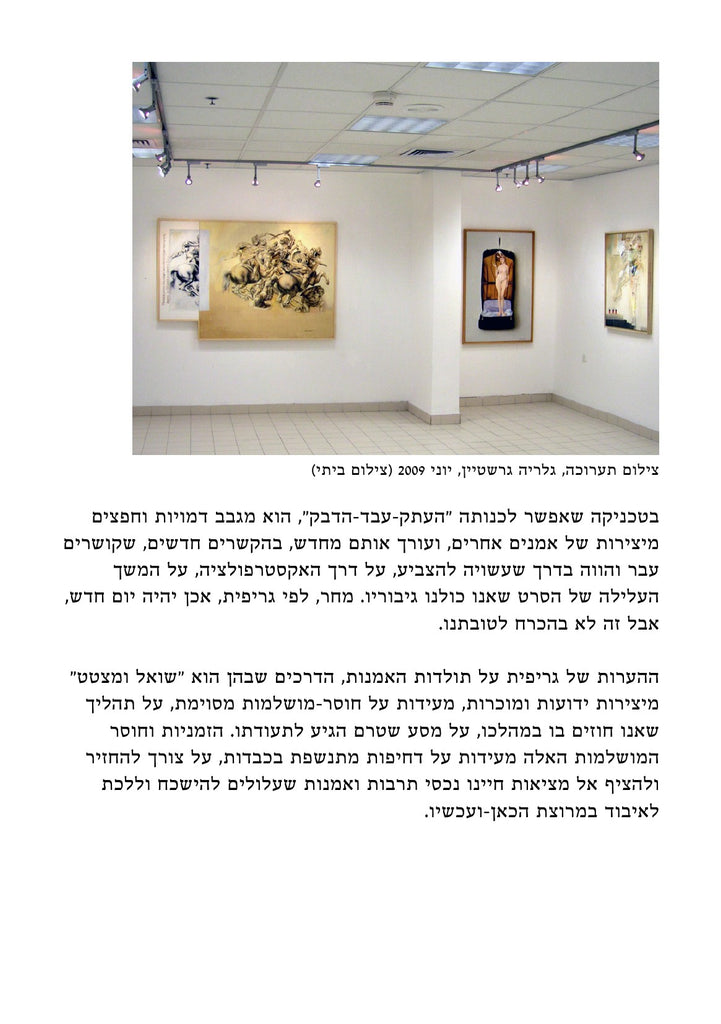

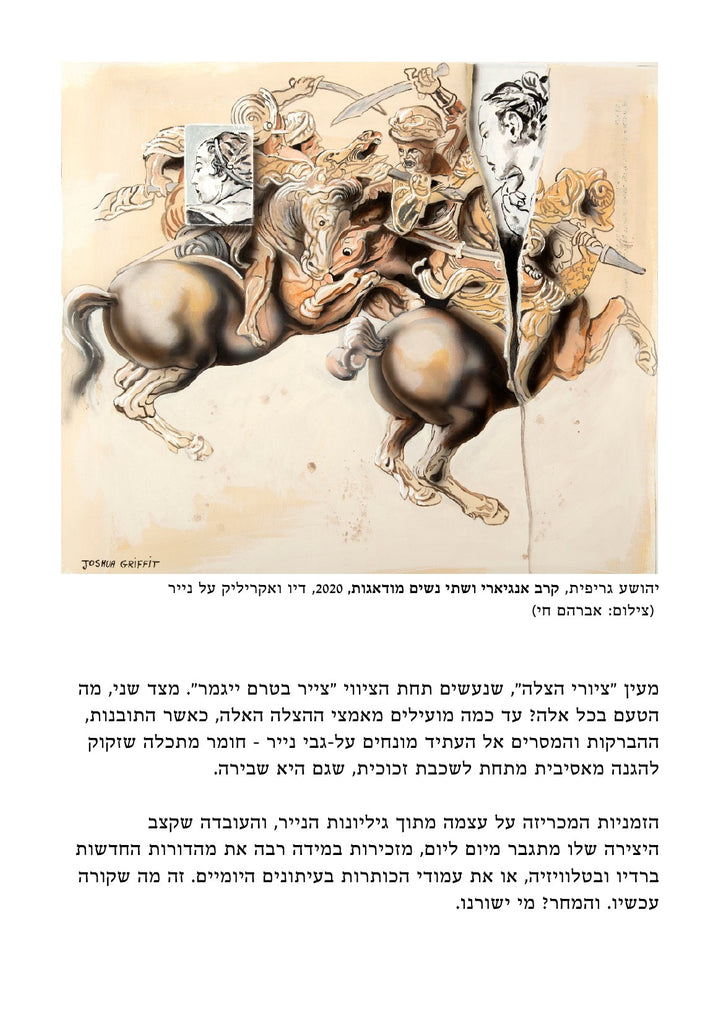

In a technique that could be called “copy-process-paste,” he stacks figures and objects from the works of other artists and restructures them in novel contexts that connect past and present, in a way that may indicate, through extrapolation, the continuation of the movie plot in which we are all the heroes. Tomorrow, according to Griffit, is, in fact, another day, but it will not necessarily be fortunate.

Griffit’s comments about art history, the ways in which he “borrows and quotes” from well-known and familiar works, reveals a certain imperfection – a process that unfolds as we observe, a journey that has yet to reach its destination. This transient nature and imperfection imply a heavily panting urgency, a need to bring back and flood into the reality of our lives cultural and artistic assets that may have been forgotten and lost in the here-and-now. His works are “rescue paintings” of sorts, made under the edict: “Paint before it disappears.”

On the other hand, what is the point of all this? How beneficial are these rescue efforts, when the insights, flashes of brilliance and messages to the future are all set on paper – a perishable material that requires massive protection under a layer of glass, ' which is itself fragile?

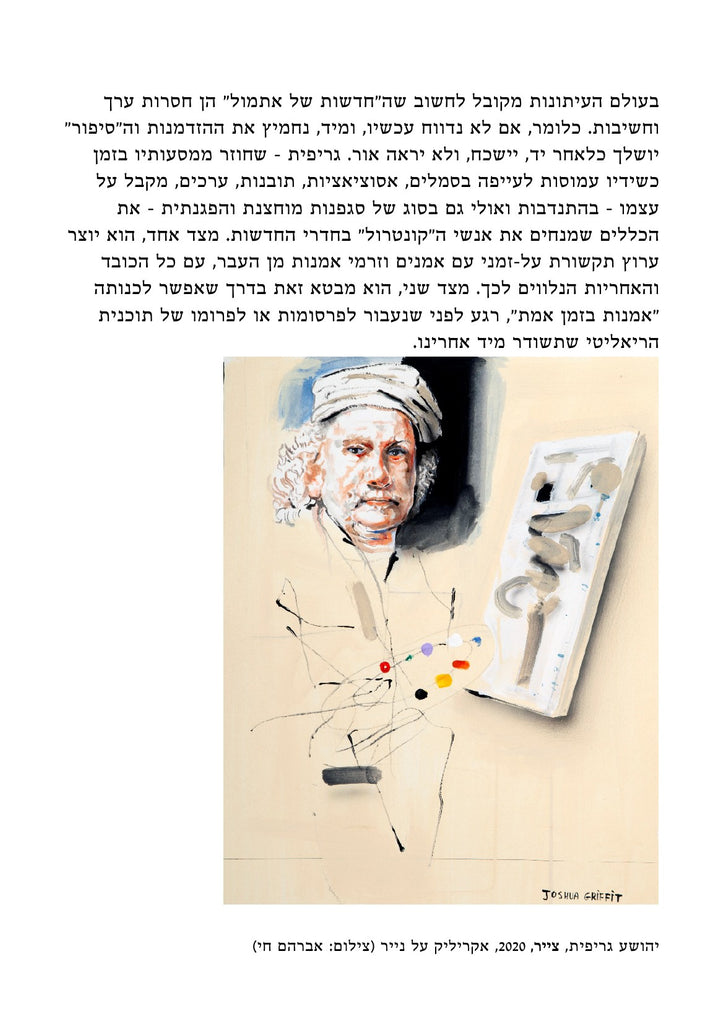

The self-proclaimed transient nature emerging from the sheets of paper and the fact that the pace of its creation quickens day by day, eminently recall the breaking news on radio and TV or the headlines in the daily papers. This is happening now. And tomorrow? Who knows?

In the world of journalism, it is common to think of “yesterday’s news” as worthless and unimportant. That is, if we don’t report it now, immediately, we would miss the chance and the “story” would be thrown out, forgotten and not see the light of day. Griffit – returning from his time-travels laden with symbols, associations, insights and values – obligates himself, voluntarily and perhaps even with a kind of extroverted and demonstrative asceticism, to observe the rules that guide newsroom control teams. On the one hand, he creates a timeless communications channel with artists and art movements from the past, with all the accompanying consequence and responsibility. On the other hand, he expresses this in what might be called “real-time art” – between the commercial break and promo for the reality show that will follow.

For example, in one series of works, the daily sights of fields in the Israeli land adjacent to the Gaza Strip blow bitterly across our faces, facing the wind. The smoke infuses helpless anger, contrasting sharply with the 1960s cars that Griffit plants for us at strategic points in the composition. These nostalgic peels (“ah, the good old days”) return us to the days of innocence, when a burning field was considered a disaster that no one would dare accept.

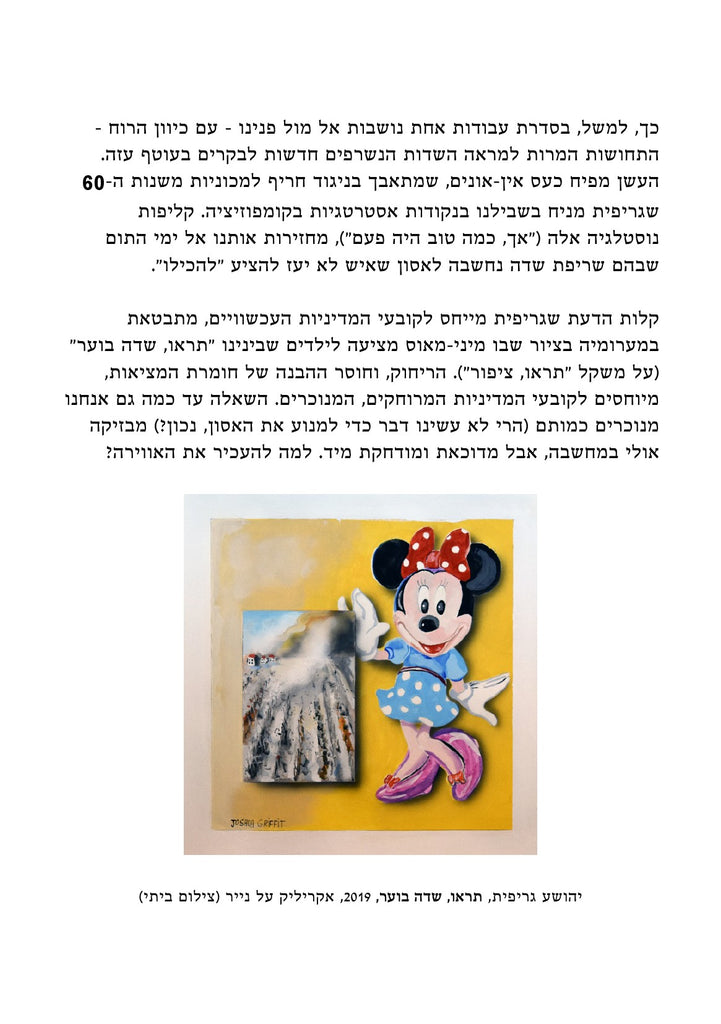

The foolishness that Griffit attributes to today’s policymakers is exposed in a painting in which Minnie Mouse tells the children among us “Look, a burning field!” (As in “Look, a bird!”). The detachment and the lack of understanding of reality’s harshness are attributed to the distant, alienated decisionmakers. The question of how estranged we ourselves are (we did nothing to prevent the disaster, right?) may flash in our thoughts, but it is immediately suppressed and repressed. After all, why contaminate the atmosphere?

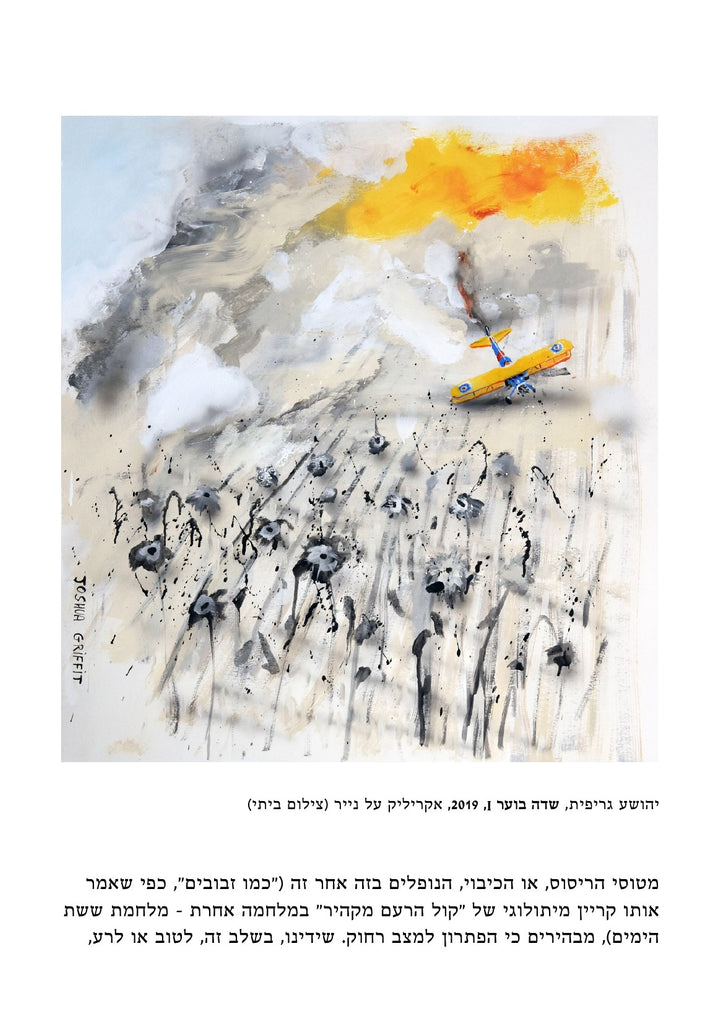

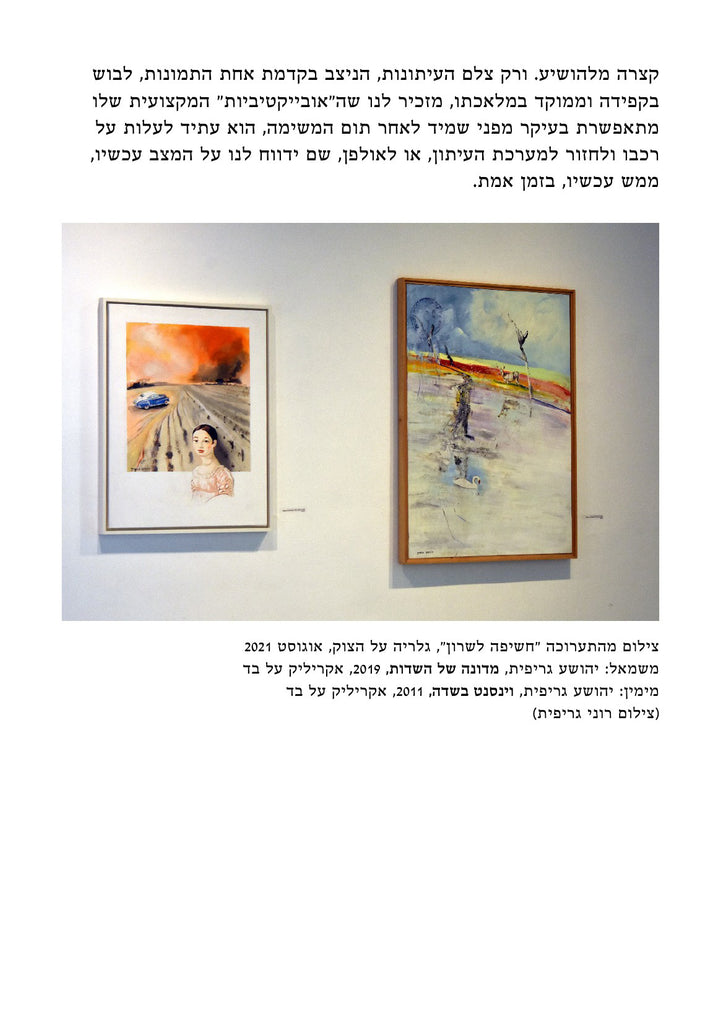

The pesticide-spraying or firefighting planes drop, one after the other (“like flies,” echoing the mythological blood-curdling threats of “The Voice of Thunder from Cairo” from yet another war – the Six Day War), making it clear that the solution is distant. That we are, at this point, for better or worse, incapable of making a difference. And only the photojournalist, standing in front of one of the pictures, meticulously dressed and focused on his work, reminds us that his professional “objectivity” is possible mainly because immediately after the assignment, he will get into his car and return to the newsroom or studio – from where he will report about the current situation, what is actually happening now, in real time.